Imagine All Angles: The Shift from Victimhood to Agency in Tracks about Infidelity

Taylor Swift and Dante's Inferno come together to discuss the power and politics of cheating

Taylor Swift has often been accused of “playing the victim” and “twisting her narrative” to make herself the innocent party or paint herself in more favorable light. Although she was particularly accused of this in her early career, it continues to be one of her detractors’ most frequent arguments: Taylor Swift acts like she’s been wronged. She doesn’t take responsibility. Even as recently as 2024, an article on The Daily Beast asked, “Is Taylor Swift ‘Playing the Victim’ in Her Masters Dispute with Scooter Braun?”

(Honestly—I cannot even. It was her own music. That she made. But, I digress.)

This blog is not here to debate Taylor Swift’s character, as it focuses solely on the music, and even more specifically the lyrics, to point out trends and patterns that exist in the primary source material; we never assume authorial intention.

The lyrics, without a doubt, show a distinct shift from victimization to agency over the course of the albums. The most obvious examples of this shift come through the narrators who speak about infidelity.

The discovery of an infidelity is often a painful turning point in a relationship. It represents the loss of the belief in the commitment and the betrayal of foundational trust with a very close, intimate partner who may be an attachment figure. Having an attachment bond severed so quickly causes intense emotional pain, and it disturbs the feelings of security upon which humans build their lives.

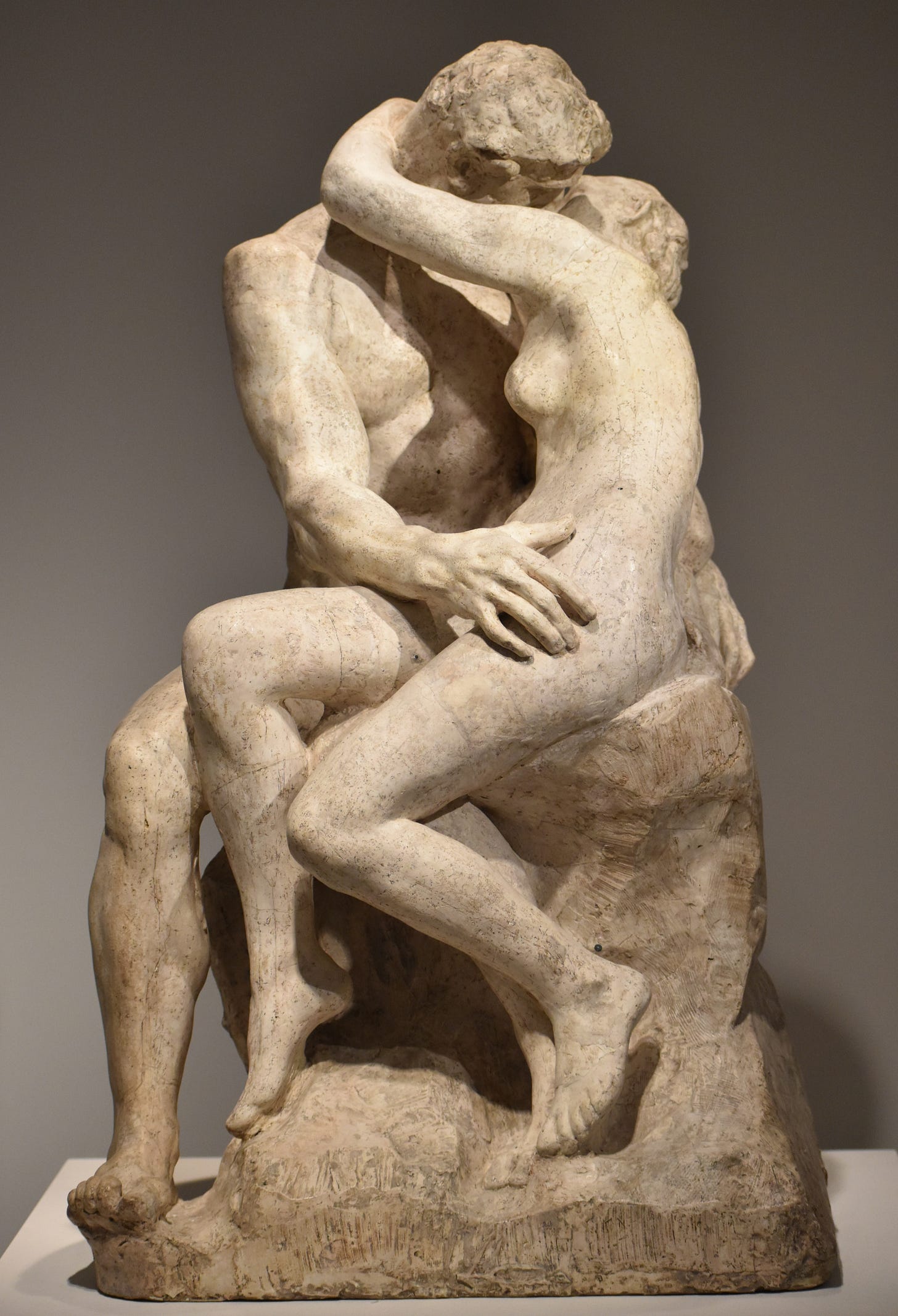

Adultery has historically been considered a sin not only because it is a betrayal, but also because it indicates that people have succumbed to their passions. When Dante descended into Hell in his poem Inferno, among the first sinners he encounters are the lovers Paolo and Francesca, who are whirling in a tornado of bodies, endlessly making love. This is the circle of the lustful, and Francesca speaks to the Dante-pilgrim, describing her story.

(Also, the parallels between Dante-Poet / Dante-Pilgrim and Taylor-Songwriter / Taylor-Narrator are very interesting, and will hopefully be discussed in the future.)

Francesca was forced to marry a man named Giovanni, but soon, Francesca and Giovanni’s younger brother Paolo fall in love. They read together from the tales of King Arthur, about the affair between Guinevere and Lancelot—the affair that brought down Camelot. When they read of this unavailable yet undeniable love, Francesca and Paolo put down the book and—they kiss.

Then, Giovanni finds them in their lover’s embrace. And murders them both.

That’s how they end up in Hell, where Dante finds them.

Humans can debate endlessly whether it’s worse if the cheating is physical or emotional, premeditated or accidental, once or recurring. There is no hierarchy of pain; all infidelities leave deep marks. They represent the betrayal that undermines the commitment people have made to each other. The sense of safety is ruptured, and it takes concentrated, purposeful effort to repair, if the parties are interested in repairing.

There are three categories of cheaters in the Taylor Swift canon: those who have been cheated on, those who cheat with, and those who are cheaters. The increasing complexity of Swift’s portrayals of infidelity over time show a shift from victim to agent, from accusation to responsibility.

The Victimhood of the Betrayed Party

The earliest portrayal of infidelity in the Swift canon is “Should’ve Said No.” Other songs on the debut album, like “Picture to Burn,” reckon with heartbreak but are not specifically about infidelity. “Should’ve Said No,” however, clearly describes this triangular scenario. The narrator has discovered the secret of the betrayal, and tells the cheater, “you should’ve known that word / of what you did with her / would get back to me.” The song takes place while the cheater attempts to deliver a too-late apology, which the narrator rejects.

And in “Should’ve Said No,” the narrator is clearly in the position of the “cheated on,” which, in this case, is the role of the victim.

This narrator sees no complexity here: he cheated, I leave him. End of story. He should not have cheated—hence the song title, “Should’ve Said No”—because it was wrong, and it was bad. It was lustful, and it broke the commitment, as we learned from Inferno. The narrator has been “crying” and the cheater is “begging for forgiveness at [her] feet.” There is no repair or resolution possible here. It’s “You should’ve said no, baby, and you might still have me.” But obviously, the cheater was disloyal, so the narrator is severing the relationship, despite the apologies, which we assume to be insincere based on the actions.

The next clear example of this comes in the song “Babe,” written by Swift but originally released by the country duo Sugarland, and then included on the Red (Taylor’s Version) album as a vault track.

This song is relatively vague on the betrayal until the bridge. Finally, the narrator divulges: “Since you admitted it / I keep picturing / her lips on your neck / I can’t unsee it.” We become clear that this betrayal is specifically infidelity, where the lover has cheated with another woman.

The narrator is clearly distraught, sitting on the kitchen floor, wondering where things went wrong. “Your secret has its consequence / and that’s on you, babe,” she sings. So, again, the narrator is in the position of the victim, and is suffering, and is pinning the blame on the cheating partner without any complexity or questioning.

“Babe,” as it is more vulnerable and more willing to sit in the difficult feelings, is a more emotionally complex song than “Should’ve Said No,” but neither has the narrator taking any responsibility, or even wondering if such a thing is possible. The narrator remains purely in a state of victimhood; the narrator has been wronged, and in being wronged, is suffering, and calling out the perpetrator’s sins.

After “Babe,” Taylor-narrators have no more emotional energy to waste on cheating men. They stop being the victim and instead begin to create victims of their own, specifically murder victims, who are the cheating husbands.

Murdering becomes the preferred method of dealing with men who cheat—and these men are repeatedly taken to task in the canon. In “Fortnight,” the narrator casually mentions, “My husband is cheating / I wanna kill him.” In “Florida,” “your cheating husband disappeared” mentioned alongside the “lace and crimes” of other women. On evermore, “no body, no crime” murders Este’s husband, who is mentioned as having a “mistress” after he has killed his wife, a real eye-for-an-eye cheating situation, while showing that Taylor-narrators are taking matters into their own hands. No longer crying over cheating men, no longer lamenting the promises they made. Instead, these narrators are ready to kill.

“Vigilante Shit” further heightens this dynamic, opening with the line, “Draw the cat-eye sharp enough to kill a man.” It describes a vigilante narrator dedicated to righting (writing) wrongs. It appears that the man in the song has wronged the narrator by cheating on his spouse with her; “You did some bad things, but I’m the worst of them.” He is labelled as a “liar,” and in the second verse, the narrator outs him to the wife.

I find the second verse to be vague enough—the “cold hard proof” that comes in an envelope may be more closely related to the “white collar crimes” of the man than his infidelities. But either way, because he is called a “liar,” we can say that he betrayed his spouse, although I will admit in this song it could be an infidelity, or it could certainly be another kind of betrayal, like a financial one.

When it comes to this betrayal, the Taylor-narrator sings, “Don’t get sad, get even.” This is a far cry from the on-the-kitchen-floor crying of the victimized narrator of “Babe.” Although killing is only mentioned in the first line of “Vigilante Shit,” this narrator is taking action, not allowing herself to be the victim any longer. She takes down the cheater without remorse.

Our Changing Perspective of the Affair Partner

Compare the narrator of “Vigilante Shit,” who takes sides with the wife, to the narrator of “Better Than Revenge,” from Speak Now. “Better Than Revenge” was disparaged as problematic for its original line, “She’s better known for the things that she does on the mattress.” The whole song has been noted as misogynistic and slut-shaming, making it another woman’s fault that the boyfriend cheated. Obviously, the boyfriend had agency and made his own decisions, so the woman is not entirely to blame.

“Better Than Revenge” is particularly immature; that’s part of its theme. It talks about “stealing other people’s toys,” and “the playground,” making the narrator sound petty and childish. The song itself is the revenge; calling out the other woman is how the narrator asserts her power. And this too, is problematic, because the other woman doesn’t have a voice with nearly as much reach.

The song also has been noted for a lack of awareness around patriarchal norms that pit women against each other and cause competition over men. Swift changed the line on Speak Now (Taylor’s Version) to “he was a moth to the flame / she was holding the matches.” Even with the change, the lyric still implies that the agency belonged to the woman who entranced the boyfriend away, leaving the Taylor-narrator victimized.

The narrator of “Better Than Revenge” held the other woman responsible; by “Vigilante Shit,” she knows better, and she takes sides with the wife. Having empathy for the other woman is one of the ways that Swift has complicated this shift from victimhood to agency in the realm of infidelity.

In “mad woman” from folklore, for example, the mad-woman-narrator sings, “The master of spin / has a couple side flings / good wives always know / she should be mad / should be scathing like me / but no one likes a mad woman / what a shame she went mad.” Now, the narrator is aware of the toxic, patriarchal dynamics that lead women to feel in competition over men. Here, the “good wife” has knowledge of the infidelity, and is at least able to make her decisions based on the knowledge, with slightly more powerful than the blind-sided narrator of “Should’ve Said No” or “Babe.” Swift weaves in these lyrics to show us that women are not always the victim; sometimes, they are using the knowledge of the affair for tactical advantage or because the marriage gives them a power they cannot sacrifice in the patriarchy. We can empathize with the betrayed person in a different way, which the narrator shows.

Although I don’t think “happiness” is specific about the relationship ending because of infidelity, there’s a line I really love that says, “I haven’t met the new me yet,” meaning both that the narrator hasn’t met the new person she herself will become in the wake of the relationship, and she also hasn’t met the woman who will replace her.

The song is not specific enough to say that it is about infidelity (whether the “new me” came along before or after the end of the relationship), but it is particularly emotionally complex, finally holding the conflicting emotions all at once: “there is happiness after you / there is happiness because of you, too / both of these things can be true.” The narrators graduate from a kind of one-way morality, where the action of betrayal defines the person as bad, to a rising “above the trees,” to accessing a higher plane of the self, and seeing myriad angles.

Although she is sad, this narrator is not devoured by her victimhood; it is not her whole identity. She even ends the song with a hopeful image, a “glorious sunrise,” where the sun can dawn on a new era of her identity as a whole person.

Infidelity and Shifting Empathy in the folklore Triad

On folklore, there is famously the triad of “cardigan,” “betty,” and “august,” where James and “august” have a summer romance, and James’s girlfriend Betty finds out, via her friend Inez.

Betty is the “victim” in this situation, the one who knew nothing of the affair and is left heartbroken. Yet “cardigan” is nothing like “Should’ve Said No” or “Babe” in the way it imagines the one who suffered the betrayal. Betty’s refrain is the tongue-in-cheek “when you are young they assume you know nothing.” But Betty is not the unknowing victim; she knows lots of things, which she describes over the course of the song.

Betty even has the perspective to know that James is not patently “bad” because he cheated. The chorus is “When I felt like I was an old cardigan under someone’s bed / you put me on and said I was your favorite.” So James is capable of making Betty feel special, even though he has caused her pain.

Betty was the victim of James’s cheating summer, but she is also entirely her own person. The narrative does not revolve around what happened to her. It revolves around the things that she knows, which are many. She can see this narrative has larger patterns, like “Peter losing Wendy,” a story that has played out before. She can see that James has his own hurts. The line, “Leaving like a father / running like water” is not specific about whether it’s Betty’s father or James’s who might have been running away, but as trauma begets trauma, she is able to see with much larger perspective: hurt people hurt people.

In fact, it’s not until the end of the song that she recalls the pain of the betrayal. She sings, “I knew you’d miss me once the thrill expired / and you’d be standing in my front porch light / and I knew you’d come back to me.” Again, it is the knowing that empowers her, that shifts her from victim to agent. The information withheld from the narrators of “Should’ve Said No” and “Babe” kept them in the dark; Betty is our knowing narrator, who is in the (porch) light.

In folklore: the long pond studio sessions, Taylor Swift said that she thinks Betty and James end up together. That even after the pain James caused Betty, he apologizes, and they repair their rupture.

James wants to make himself the victim. He says, in “betty,” “She said, ‘James, get in, let’s drive’ / those days turned into nights,” as if the narrator of “august” made him do it. But James had agency; he chose to get into the car. James, the cad, the hangdog boy on the porch, gets his summer romance and gets his steady Betty too. So, he is not the victim here.

So—if Betty is not the victim, and James is not the victim, that leaves us with “august.”

The narrator of “august” is unnamed. In folklore: the long pond studio sessions, Taylor Swift says that she thinks of her as “Augustine,” but she is not given a name in the song. This is important because the narrator of “august” is portrayed as the one who is truly the victim in the triangular situation, and this is one of the ways that we see victimhood and agency becoming more complicated over the course of the albums.

The narrator of “august” meets James and has a romance with him “behind the mall.” She romanticizes it in her song, track 8 for August on the album, where she describes being “twisted in bedsheets” and how “august slipped away like a bottle of wine.” But “august” also contains something much sadder.

The line “never have I ever before” implies that the narrator of “august” is experiencing this love, romance, and physical touch for the first time. Remember the pain caused in “Fifteen,” on Fearless, when “Abigail gave everything she had / to a boy who changed his mind”? The narrator of “august” seems likewise headed for a painful downfall. She “cancels [her] plans just in case [he] call[s],” and recognizes that “you were never mine.”

While James and Betty retain their couple privilege, the narrator of “august” is the one with the least power. Although she doesn’t paint herself as the victim, she nonetheless evokes the listener’s sympathy. This is an interesting layer of complexity in the infidelity tracks that shifts our attention from the cheated-on to the cheated-with.

Just two tracks later, “illicit affairs” imagines a narrator who is involved in an affair, much like “august.” The song is written in second-person, as if the narrator is speaking to herself, or as if an older, outside perspective is describing this incident. I am going to use the term “narrator” even though we could just as easily say “protagonist,” here. There is a shift to the first person at the very end of the song that suggests to me that the whole song is written in second-person as a way for the narrator to remove herself from an intensely painful situation.

This song hurts; it is easily as painful as “Babe,” or even more so. We have a sense that the narrator does not have any of the power in the situation. She is called “kid” by the lover, for example, and must purposefully hide the romance from anyone by wearing a hood and leaving no trace of scent, “like [she] do[es]n’t even exist.” She picked out the perfume “just for him” but cannot wear it.

Her pain seeps into every line of the song. The affair started in “beautiful rooms” and has now degraded to “parking lots” (perhaps, for example, behind the mall). It likewise used to give a “mercurial high” that is now “dwindling.” The refrain changes slightly each time, but each one shows how painful it is. First, the “illicit affair” “dies and it dies and it dies,” and then it “lies and it lies and it lies.”

By the end of the song, the narrator is reduced to a “godforsaken mess” and an “idiotic fool,” who would “ruin [her]self” for the lover. It’s a humiliation, a story of degradation and powerlessness. We can imagine this lover in the position of “august,” or in the position of one of the affair-partners in “madwoman” or “Vigilante Shit,” a person taken advantage of by someone with much more power.

In this case, we shift our empathy for the victim not to the cheated-on spouse, but to the affair-partner. This reversal is an important shift in recognizing how the harm of infidelity doesn’t only lie with the one who is betrayed. It is a self-betrayal to cheat-with. It is as if we can imagine “Better Than Revenge” from the other woman’s perspective. There are also power dynamics to consider, which cause harm to any less-powerful parties.

Expanding Empathy to Cheaters

There is yet another shift in empathy with the narrator of “ivy.” This narrator, as mentioned in a previous essay, is the infidelitous spouse. She is clearly married, as they “drink my husband’s wine,” a euphemism for, you know, going down on each other. In this case, we have the sense that the husband is unsafe; he’s going to be so angry if he finds out, and burn the house down.

This brings us back to Paolo and Francesca, of Dante’s Inferno. Francesca, the wife, forced to marry a man for her father’s political alliances, fell in love with her husband’s brother. In Dante’s time, she was a sinner, one who succumbed to lust, and she should set an example for others to avoid a similar fate by overcoming their passions.

Something shifted, however, in the 19th century. Romantic poets, painters, musicians, and playwrights all latched on to the story of Paolo and Francesca, not as a cautionary tale against the passion of adultery, but as a story about a woman claiming agency in a difficult marriage. Because Romantics believed in living a life of passion, someone who succumbed to passion was not failing but succeeding at living a good life. This made Francesca not only a tragic figure, but a heroine.

She was immortalized in paintings, music, and sculpture as a woman with agency, a woman with a perspective that deserved to be centered, even in the openness of her lust. Perhaps this is part of why “ivy” feels like it takes place in a previous century, with its Romantic overtones.

We can think of the narrator of “ivy” in the same way; yes, she is overcome by her passion for the beloved in the song, and she betrays her husband. But the husband is violent, so we don’t fault her. In fact, we root for her. She has agency. She is not a victim of her passions; she is choosing to move toward love.

So now our empathy lies with the person who is the cheater. Gasp! This is a complete reversal from “Should’ve Said No,” which vilified the cheater and could not imagine any other interpretation.

Like the narrator of “ivy,” the narrator of “High Infidelity” also has agency. Her husband is not necessarily violent, but he is neglectful, absent, unloving. There was a storm on their wedding day, which the narrator considered a “bad omen,” but he was a “good husband,” and it “seemed like the right thing at the time.” Now, trapped in the image of a perfect life, she is “at the house lonely,” and sings, “your picket fence is sharp as knives.”

This narrator sings in the chorus, “You know there’s many different ways that you can kill the one you love / the slowest way is never loving them enough.” While slowly wasting away from a lack of attention, the narrator has sought the love that is lacking in her marriage somewhere else, and she says, “he brought me back to life.”

While I don’t find the narrator of “High Infidelity” particularly likable, that is part of the point. We’re not, like in “ivy,” swept along with the story. We’re left thinking and wondering—who is in the right here? Who is wrong? The bean-counting betrayed spouse is not likable either, but that’s no reason to cheat. There were other solutions; she could have talked to him, gone to counseling, asked for a divorce. The point is not so much whether or not we empathize with her, but that she is a person with agency, expressing her choices. She is not someone sitting, crying on the kitchen floor. She is not claiming victimhood; in fact, she is announcing her failings, openly. She is giving her side of the story, and taking responsibility for her actions.

“High Infidelity” is a nod to the novel and film High Fidelity in which the protagonist, whose girlfriend has left him, must reckon with whether or not he is capable of commitment. He ultimately chooses to settle down with his partner, whom he recognizes as his reality, while other women are merely fantasy. “High Infidelity” could be said to imagine the perspective of the partner, who has felt unloved and neglected while her partner fantasized about these other possibilities.

Although she justifies her cheating because she is in a loveless relationship, she doesn’t apologize for it; this isn’t “Back to December.” She is simply states the facts of it, wondering what she owes the spouse she cheated on, asking, “Do I really have to chart the constellations in his eyes?”

In the age of “Should’ve Said No,” the Taylor-narrator had a one-track mind about cheating, that it was bad and you shouldn’t do it. But now, through these multiple perspectives, we can see that there are many ways to empathize with the different players in any given scenario of infidelity.

Depending on power dynamics, our empathy may lie with the betrayed partner, who knew nothing about the affair, or with the affair-partner who will be cast out in order to keep the privilege of the couple. We might even root for the cheaters, given the right context and from the right perspective, just as we can empathize with Francesca, who fell in love with Paolo, and who was murdered by her husband.

Continuing to say that Taylor Swift makes herself the victim, however, is simply no longer true. There are mentions of infidelity on The Tortured Poets Department, such as the line in “How Did It End” that says, “We fell victim to interlopers’ glances,” but this is merely circumstantial, “lost the game of change / what are the chances.” It’s no longer the central story. Where she once relied on her music as a form of “revenge,” she now uses it to help us expand our empathy and to think about where we have power and agency, and how the choices we make affect others. Her narrators take responsibility, owning their actions, and, of course, murdering men who cheat.

Reference: Before Romeo and Juliet, Paolo and Francesca Were Literature’s Star-Crossed Lovers, by John Paul Heil. Smithsonian Mag. Nov 3 2021. Link.